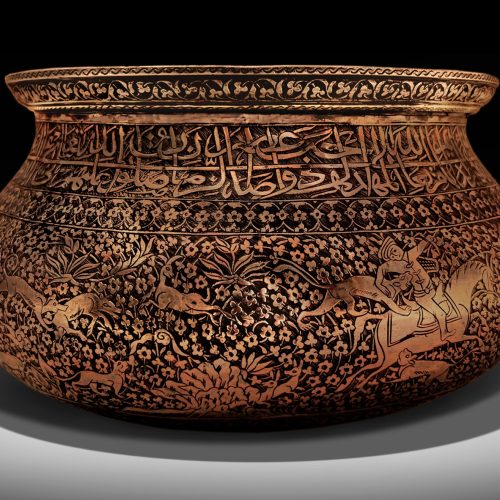

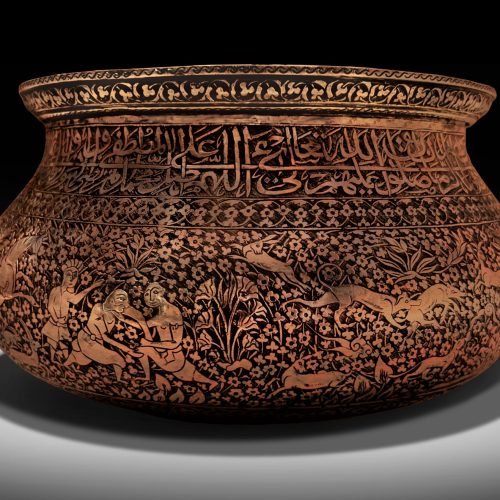

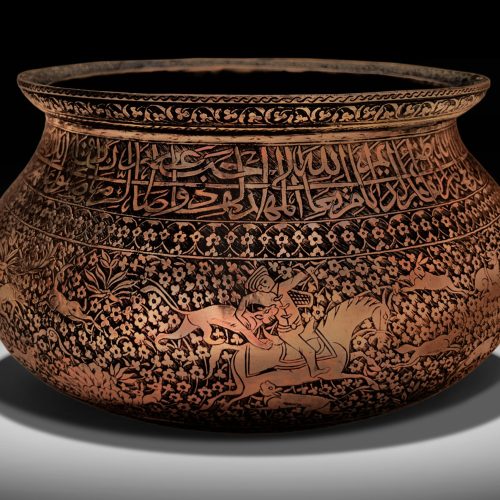

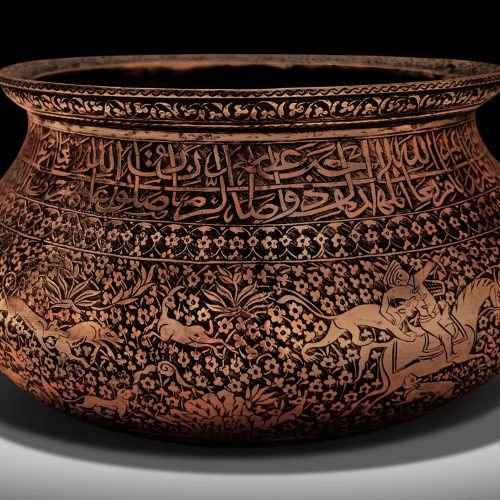

| Footnote: | In the Safavid period, shapes and decorative vocabulary continued into the early 17th century under Shah ʿAbbās I (996-1038/1588-629). A common type from this period is a wine bowl with a shallow foot and flaring lip. Lamp stands, bowls and other vessels were typically decorated with repetitive vegetal and abstract patterns similar to those found in contemporaneous manuscript illuminations and bookbinding or on carpets. Human and animal figures are once again a primary means of decoration and are comparable to contemporary drawings and illustrated manuscripts. Such engraved pieces occasionally bear Armenian inscriptions alongside the more common Persian verses; they probably belonged to members of the Armenian community established by Shah ʿAbbās in New Julfa (see JULFA) on the southern edge of Isfahan (Melikian-Chirvani, 1982, pp. 272-73). The style associated with the reign of Shah ʿAbbās lasted throughout the 17th century, as demonstrated by several objects, including a covered bowl dated 1089/1678-79 in the Victoria and Albert Museum (Melikian-Chirvani, 1982, pp. 336-37). These wares are usually attributed to western Iran, more specifically to Isfahan, because of their similarity to other arts produced there or on account of their Armenian inscriptions. Some engraved and tinned wares dateable to the late 16th century or the early 17th century have been ascribed to Khorasan, as their inscribed owners’ names include references to places in that region. They are decorated with the same type of abstract and figural ornament found on objects from western Iran, but the design is organized in a more spacious manner and always includes cross-hatching. The dates and attributions for many later 16th- and 17th-century wares are open to question. In contrast to the 15th- and 16th-century pieces, their inscriptions often supply the name of the owner but rarely contain artists’ signatures or clues to the provenance (Melikian-Chirvani, 1982, pp. 303-55). A group of cut-steel objects overlaid with gold can be associated with western Iran in the 16th and 17th centuries. Beginning in the 16th century, cut steel was used to make vessels and especially pierced plaques, medallions, and standards. The decoration of such objects is better related to contemporary cut and gilded armour than to engraved brass and tinned wares of the same period (Allan and Gilmore, pp. 253-81, 294-97). Early modern metalwork. Thousands of pieces of metalwork produced under the Zand and Qajar dynasties have survived, but they are of modest merit, generally utilitarian brass and copperware except some fine examples of cut-steel, including copies after 17th-century pieces (Allan and Gilmore, pp. 319-20). |

|---|