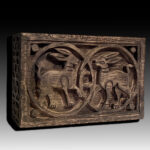

A FATIMID CARVED WOODEN PLAQUE WITH TWO HARES

PERIOD :

EGYPT, 11TH-12TH CENTURY

ORIGIN:

FATIMID

DIMENSIONS:

16.6 by 26 by 6.5cm.

DESCRIPTION:

The wood was carved in deep relief with two entwined roundels containing mirrored hares, on a thick rectangular block, through the interior, the reverse with the vertical carved band and concave roundel, remnants of old hexagram deeply carved with the closed boundary framed on each side of the block known as collector’s labels and maker symbol.

FOOTNOTES:

Fatimid Egypt saw a great flowering of wood carving (Lamm 1936, pp.90-91). Developing from Coptic and Tulunid styles, Fatimid woodwork is characterised by a more complex texture and a wider iconographic repertoire. The use of figural motifs becomes more frequent and varied, as artists experimented with depth, created sharper incisions, and developed multiple overlapping fields to integrate figures within increasingly elaborate abstract structures. Surviving examples of Fatimid wood carving are primarily associated with architecture, being friezes, door panels and surface panels around beams. Consequently, precious pieces of Egyptian woodwork that have withstood decay and destruction over the past millennium are often preserved in situ, in Coptic churches, mosques and secular buildings. Although long since eroded, evidence for painting is provided by traces occasionally still detectable on some examples. It has been suggested that many carvings were repurposed from earlier eleventh-century Fatimid palaces in Cairo. Indeed, a pair of hares facing one another akin to the present carving can be found in one of these wooden friezes reused at the end of the thirteenth century in the hospital of Qala’un, now in the collection of the Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo (inv. no.12935, see Paris 1998, pp.88-89).

The representation of animals such as the hare is very commonly found in Fatimid art of different media (Grube 1962, pp.92-93). Appearing in everything from ceramics to textiles to manuscripts, in Islamic literature, the hare has the symbolic meaning of good luck, fertility and prosperity in general, and the representation of it in the visual arts may reflect, directly or indirectly, this symbolism. Some art historians go as far as identifying the hare as an Islamic motif of paradise, based upon its frequent presence among vegetal grapevine motifs and similarities with Christian symbolism (Dodds 1972, p.75). The animal’s significance, however, was not likely to have been fixed, especially considering that the motif can be traced back to the oldest forms of Egyptian art. Though not exclusive to the Fatimids, hares are less numerous in Umayyad and Abbasid art and infrequent under the Mamluks.

Some of the most convincing visual parallels with the creatures in the present panel can be found in works in ivory. Although documentary evidence is lacking, the overlap of themes and carving techniques suggest that craftsmen worked in both media (Contadini 1998, p.113). ‘Siculo-Arabic’ oliphant hunting horns, for instance – believed to have been made in southern Italy by Arab craftsmen associated with the Fatimid sphere – not only feature similar hares, but hares strutting in interlaced roundels very close to the structures in present work. Examples of the ‘Roundel Design’ stylistic sub-group identified by Avinoam Shalem that include hares enclosed in roundels elegantly looped together can be found in the collections of the Berlin Museum für Islamische Kunst, the Louvre, Paris and the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (Shalem 2004, pp.71-77, figs.24, 27, 39). Whether the parallel is a result of direct contact with Fatimid art in Egypt or a translation of portable textiles and ceramics made in Egypt widely available in the Mediterranean (Hoffman 2011, p.103), the dissemination of the spry yet graceful creatures found in the present carving is testimony to the decorative reach achieved by Fatimid art.

Please note that this lot is accompanied by a radiocarbon dating measurement report dating the wood with a 95% confidence interval between 642-764 AD and a 65% confidence interval between 653-676 AD.

This suggests that this wooden panel must be a piece of repurposed timber from an earlier building. The tradition of using recycled building materials (stone, marble and wood) was well established in Muslim Egypt, starting with the first congregational mosque of Amr, and continuing throughout the Abbasid, Fatimid, Ayyubid and Mamluk periods. There are even examples of recycled Pharaonic blocks of masonry carved with hieroglyphs incorporated into the Fatimid city walls. The enforcement of a series of Papal embargoes on potential war materials, including European timber (used for ships and fuel) throughout the Crusades (1095-1291) meant that wood became an even rarer commodity, further promoting the tradition of reusing seasoned timbers from preexisting or demolished structures.

CONDITION REPORT:

The wooden block is fragmentary, with visible signs of wear and lying cracks in the wood, a slight splinter on the exterior scratches to the reverse, and underside with marks from previous use, as viewed.

PROVENANCE:

Private collections